A Little Data, A Few Recommendations, And A Big Dumb Object

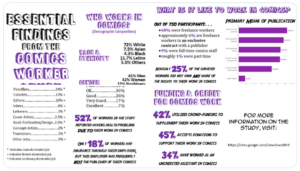

- Sasha Bassett is a PhD student at Portland State¹ specializing in gender, organizations, and pop culture. Know where you’re seeing a lot of intersection of those three things these days? Comics, which just happens to be a focus of Bassett’s interests. We’re bringing it all up today because of a recent tweet by Bassett on a study of who works in comics, and what their status as workers (for hire) vs creators (with ownership interest in their work) might be, along with a fun fact or two.

Obviously, there’s a hell of a lot of detail behind those four graphics and the very top-level summary, which Bassett is happy to share with you. If you’re interested in the people reading comics as opposed to those making them, Bassett’s got you covered there, too (although the data are from 2016, as opposed to 2019 for the creator study). All in all, the rates of creators either neither owning what they work on or getting any kind of royalty explains Bassett’s use of the #UnionizeComics hashtag, which has some good info. Check it out, creators.

- Speaking of the need for unionization, which is to say, speaking of Kickstarter (and lots of you are, cf: The Very Sexy Brad Guigar and Los Angeles resident Dave Kellett on same), you’re starting to see projects launch with explicit acknowledgement re: the Kickstarter Union and taking their lead. Case in point, Evil Twin Howard Tayler, who couched the use of KS for his next Schlock Mercenary print project in terms of following the KU’s recommendation that creators not boycott at this time.

And, since he launched said project earlier today, I’ll note that he has the same sentiment on the project page:

We are aware of Kickstarter’s position with regard to unionization. We support the unionizers at Kickstarter United, and agree with them: boycotting Kickstarter will hurt all the wrong people. Please follow those links for complete statements, and the latest information.

Tayler hedges a little, in that he doesn’t explicitly say that if the KU organizers call for a boycott during the campaign, that he’ll take it down (something I’m starting to see). Based on what he’s said publicly, I believe he would, but I also wouldn’t blame anybody that only held off starting new projects once a boycott got called rather than canceling existing ones. Tayler’s been in business long enough that I suspect he suspects what I suspect — that any action called by KU wouldn’t come until closer to a vote, most likely afterwards if Kickstarter slow-walked recognition or challenged results. But we’ll see. Now go and pledge so the guy can stop hitting F5 on his browser every coupla minutes.

- Finally, we have mentioned here at Fleen the fact that the ALA introduced a round table (their name for a working group that studies policy options and makes recommendations) for graphic novels and comics, which is one of the marks of legitimacy in the world of libraries². Via Heidi Mac’s joint, I see that the GNCRT is undertaking its first public-facing project. We’re a bit late on this — the ALA announced it four days ago, and the news made its ways into the comics press since then, and earlier today I noticed The Beat’s discussion:

The group just announced the formation of a committee to oversee a Best Graphic Novels for Adults Reading List, which will launch in 2021.

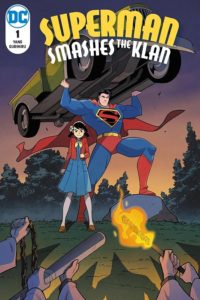

The inaugural list will highlight the best graphic novels for adults published in late 2019 and throughout 2020. According to a press release, the goal is to increase awareness of the medium, raise up diverse voices, and aid library staff in developing graphic novel collections.

On the one hand, I’d note that there’s nobody checking IDs and keeping those over the age of 18 from reading YA or even Middle Grade comics. On the other hand, I get it — sometimes, you just want a protagonist that’s no longer in the throes of (pre-)puberty confusion. The committee will look at all graphic novels published from 1 Sept 2019 through the end of 2020, and release their list at ALA’s midwinter convention in early 2021; the committee will meet throughout the year to consider works as they’re released, and presumably they’ll move to a calendar-year eligibility schedule in future.

Now here’s the part you should pay attention to:

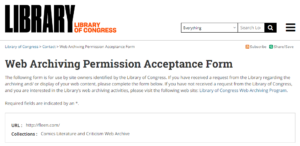

Nominations can be made by all members of the public, including committee members and ALA members though an online form that will be available in January 2020 on the GNCRT website.[emphasis mine]

The wording of the press release made it seem like we, members of the public, could also participate in the committee, but a close reading indicates it will be made up of members of GNCRT, meaning ALA members. Ah, well — I will have to content myself with making nominations through the form once it opens up. Oh, and creators? Check this out:

Publishers are welcome to submit copies of titles to the committee for review, though they are not eligible to nominate their own titles for consideration.

I’m sure you can find a loyal reader of your stuff to put your title into nomination, and if you send a couple copies along so that it’s easier for the committee members to actually read your work? Librarians use these lists to develop their collections. There are an estimated 116,687 libraries in the United States, which should be motivation enough for you to keep an eye on this program.

Oh, and in case you didn’t think to pay attention to the YALSA Great Graphic Novels for Teens (which has been going on for 15 years now), maybe you should get on that. I’m not sure anybody’s got an accurate metric on how many extra copies you should print of a title that makes the ALA lists (Spike, maybe? I’ll ask and get back to you), but I’d submit it’s the sort of problem you want to have.

Spam of the day:

Your account is listed as the recovery email for [redacted]

Nice try, lowlife. You almost made that email look like a legit security notification, but for two things: 1) the email company in question doesn’t ask me to click on links like you did, and b) you apparently think that an email address will use itself as the recovery address if something goes wrong. That doesn’t make sense! That requires more imagination than Perfect Ron Sipes talking about stumps.

_______________

¹ Also an adjunct instructor at Williamette University, and if there’s one cohort whose general overwork and poverty exceeds that of grad students, it’s adjuncts. Respect.

² Given how important librarians have been to the adoption of graphic novels and comics over the past decade or so, I’m a little surprised it took until last year.