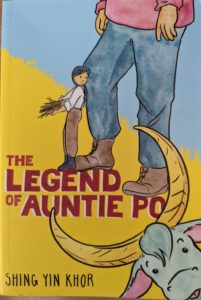

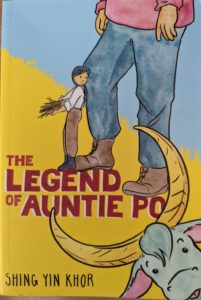

As we get started, a disclaimer. Shing Yin Khor is a personal friend of mine, and I’ve had at least the outline of this story rattling around my brain for years now, ever since we talked about it as a work in progress over some surprisingly delicious Tex-Mex in Juneau, Alaska. So when I picked up my copy of The Legend Of Auntie Po from my local comic shop last week, I had high hopes and even higher expectations.

Because one should never count out Shing Yin Khor when it comes to a) lumberjack culture; b) foodway stories; c) immigrant tales; and d) delicate, gorgeous watercolors. Combine all of those into nearly 300 pages of story, and throw a little adolescent queer longing in on top, and you’ve got an absolute winner. For those that don’t want the spoilers ahead, get a copy or three, read it until it falls apart and then read it some more.

Actually, the spoilers are going to be kind of light — it’s the 1880s, a logging camp in the Sierra Nevadas, at a time when Chinese workers were both valued for skills in large undertakings (building entire logging infrastructure, or running railroads through the tallest mountain range in the hemisphere) and simultaneously regarded as a plague upon the land, despoiling a nation out of its natural white purity.

Don’t look too closely at everybody that isn’t white, particularly those that the land in question was stolen from, or those whose parents and grandparents were stolen from overseas to work the land. The country has a myth of manifest destiny to construct here.

And that’s really the core of Auntie Po — that myth belongs to anybody that’s trying to make sense of their circumstances, whether it’s in the service of oppressing everybody that doesn’t look like you, or in trying to find a little hope at the end of the day that somebody powerful might be in your corner. Nearly everybody in the story is trying to find that bit of footing, and even the white folks haven’t been around long enough for some to count them as real Americans¹.

So they make up stories — Paul Bunyan was revered by the northwoods loggers? Hao Mei, 13 and full of imagination and stories, knows that Po Pan Yin and her blue water buffalo Pei Pei were even bigger and better. Auntie Po doesn’t just stay with Mei; when need strikes, the other children in the camp — none of the Chinese — call on her and see her, really see her. And if this newer Auntie Po is Black rather than Chinese? Well, myths take on their own lives, adapted by the people that need them and make them their own. And that carries on past the children; by the end of the book the loggers in the bunkhouse argue whose crew cut more lumber — Paul Bunyan or Auntie Po.

Mei’s father, Hao Ah, doesn’t need Auntie Po because he knows who he is — the only cook that can keep the loggers satisfied², and twice the man of the white guy that tries to replace him. Mei learns who she is eventually, too — a girl with dreams of university and learning, and also the best pie maker for miles around — and so she lets Auntie Po go, but others take her up and make her their own. Hels Andersen insisted that the Haos were family to him, and over time he changes that from empty platitude to reality, and so a little of the myth of white supremacy crumbles, at least within one logging camp in one corner of the Sierra Nevada.

It takes a long time for myths to completely die, though — and those that don’t have anything else to rely on (whether that’s true or just what they tell themselves) can fan a myth back to life if even a spark of it remains. There’s not so many loggers out there that might call on Auntie Po, but there are echoes of her, in every burned paper memorial to a Chinese logger that fell at his work, every sealed bottle with a name and birthday inside to give proper identity to an unmarked grave.

She still lives on in whispered stories that Mei let out into the world, and instead of stories of Auntie Po, Mei gets to tell her own story, which is another form of myth. Folk heroes and gods, they say, exist as long as they have believers, and even if nobody believes in Mei but Mei, that’s a big, bright blaze of belief and she will bestride her world like Po Pan Yin towers over the tallest pines. Giant blue water buffalo optional.

The Legend Of Auntie Po by Shing Yin Khor is a deeply researched³, beautifully illustrated story of a difficult time and place. Any reader that’s willing to learn about/acknowledge the origins and legacy of white supremacy at a tween-age-appropriate level will find a lot to love and a lot to think about here. Find your copy at your local bookstore or comic shop.

Spam of the day:

We are interested in your products. If your company can handle a bulk supply of your products to Cameroon, please contact us.

I can bulk supply opinions on webcomics wherever you like, sport.

_______________

¹ Logging boss Hels Andersen isn’t more than a generation and a half from Scandinavia, and undoubtedly looked down on my the moneyed class that funds his operations. Hell, I guarantee you that Laura Ingalls Wilder’s saintly Ma looked down on the Andersens and other recent arrivals; if you don’t remember her snotty opinions of recent immigrants, maybe don’t give the Little House books to the kids in your life because yeesh, Laura, her Ma, and her daughter Rose were serious nativists and Pa Ingalls was the definition of a failson locust, gaming the system and displacing humans from their land and lauded for it.

² His schnitzel is legendary.

³ If admittedly incomplete; in the afterword, Khor acknowledges the lack of indigenous characters and recognizes that the story of their presence in the logging camps is a story that needs to be told, but not theirs to tell.