I had a revelation on my morning commute about chef Grant Achatz and molecular gastronomy in general. Bear with me.

I have never previously gotten the appeal of molecular gastronomy and the mad scientists that pursue it. Sure, they have food experiences that sound unique and creative, but I’ve always wanted a meal that didn’t just transport me, but which was recognizable as food.

Food is made of basic ingredients and skill and can be recognizably reproduced by anybody with the time and patience to practice. I will never have access to the ingredients or sense of flavor or even the knife skills of a commis in a top flight kitchen, but I can roast a chicken; the differences between my roast chicken and the best roast chicken in the world will be obvious, but it’s still a roast chicken.

For me, the Grand Unified Theory of cooking revolves around the fundamental forces of heat, moisture, salt, and time; they can be manipulated in fairly fundamental ways, arranged by some fairly basic tools¹ and techniques, all of which go back through the history of human endeavour to keep ourselves fed with something that tastes good. The most commonly-used implement in my kitchen has not changed its basic structure in millenia.

This philosophy is why dinner tonight will consist of flour + water + yeast + salt, thrown on a hot rock with tomato and cheese and mushrooms, which will transform itself into something simple and satisfying and delicious. I’ll probably drink a wine made by a retired nuclear physicist who, for all the modern equipment at his disposal, utilizes techniques as old as civilization and operates on a small scale so that he can be sure that everything he produces is as good as he can possibly make it, but doesn’t want to be precious about things. He wants his wine to be shared with food by people that enjoy each other. Simple.

Topic shift: my favorite restaurants are owned by a pair of guys that have provided me more good times than I can recall². They’ve passed me more free nibbles and drinks than I can count, graciously entertained friends old and new, and at least one of their bartenders is a genius. They also do a podcast that’s really good, and their latest show features Grant Achatz, perhaps the maddest of America’s molecular mad scientists.

I won’t even get into Achatz’s frankly amazing history, from working at the fabled French Laundry to founding molecular temple Alina to the now God’s just screwing with us level irony of his cancer diagnosis — cancer of the tongue, which destroyed his ability to taste. None of that’s important right now. If you want an idea of the sort of stuff that Achatz is doing, the stuff that I just didn’t get, Lucy Knisley did a comic about the experience which you should go read now. How do you get so far from food, I’ve always wondered.

Halfway through the podcast, I was starting to get my answer. Achatz does these things not because he’s in love with technology for its own sake, but because he’s got crazy ideas and wants to see which of them might stick. Prime example: having a tablecloth made of silicone that can have food prepared directly on it and used as the servingware was a crazy idea. But it changes the interactions of diners with the food, and with each other. We’re still in Crazytowne³, but I’m understanding his POV a whole lot more. Then I got to the segment of the show starting about 43:19, and lasting around ten minutes. Go listen to it now.

See, Achatz’s major project these days is called Next; every three months, it changes to something new. The opening menu/decor/concept/everything was about recreating a classic French meal, circa 1906. Then it became for three months an exploration of Thai cuisine, just because that’s as far from classic French cooking as you can get. There was a period that explored Achatz’s youth, mid-70s in Michigan (lots of mac ‘n’ cheese and peanut butter & jelly, I’m told), and so forth. There’s no reason to keep changing what he does except he can, and it forces him to continuously up his game. He has taken an act of creation and instead of resting on success, responds by chucking it all when it gets well known and starts over again.

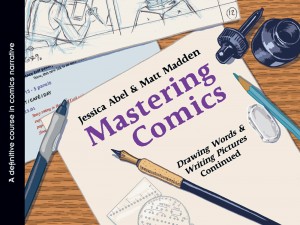

I heard that and names started to pop into my head: Gurewitch. Onstad. Beaton. The nimbleness, the reinvention, the metaphor of culinary creativeness as webcomic stretched beyond all credible boundaries and what the hell is wrong with you Gary. The he told the audience what he does when a three month rotation at Next closes.

He gathers up all the recipes, compiles them into an e-book, and sells it through the iTunes for seven bucks4. He’s made his mark, he’s not going to repeat himself, and he wants to put it out there for everybody for damn near free. This is the very model of the independent creator as driven, screw what I’ve done what can I do next obsessive.

Now I get him. Grant Achatz works in food (sometimes down to molecules). Webcomickers work in images (sometimes down to pixels). They have an infectious enthusiasm and a restless energy and a desire to share it as widely as possible. Hell, if you listen to the end of that segment and hear about the concept of “Last”, he’s even got the possibility of the equivalent of a content scraper.

So yeah, that’s where my brain’s been today. Still not enough to go eat at Alinea, but damn if my conceptions of creativity haven’t expanded a bit. And if nothing else, the bit in the podcast about the duck press was hilarious

_______________

¹ Like Alton Brown, I have only one uni-tasking tool in my kitchen.

² Also, if you can keep two restaurants afloat for a combined 27 years through the greatest recession of the past two generations, you are a steely-eyed businessguy of Khoo-like proportions.

³ The conceptual-slash-performance art district.

4 And you know what his seven dollar recipe collections won’t call for? Diode-pumped lasers in the hazardous power ranges to break shit down into its atomic components so you can put it back together in an arbitrary shape. I’m back from the molecular brink, because I can guaran-frickin’-tee that the nitrogen cooling system for that laser is the goddamn definition of a unitasker, and it is not going to appear in a recipe book made for the edification of anybody that wants to screw with the recipes. This is the culinary equivalent of a Creative Commons that permits derivative works.