Fleen Book Corner: Larry Niven Flashbacks

Why Larry Niven, you ask? Because in junior high and high school, it was a time for plentiful reprints of old ’60s SF stories, and I read pretty much everything that Niven wrote in that time period. One short story, about a protagonist named Richard Mann¹, has stuck with me. It involved ancient living artifacts of a long-ago stellar empire, trees genetically engineered to act as solid-fuel rockets to power spacecraft to explore the solar system. Also, how bad things happen when you use them to make bonfires.

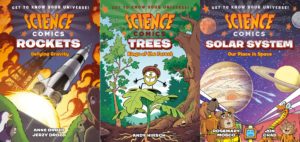

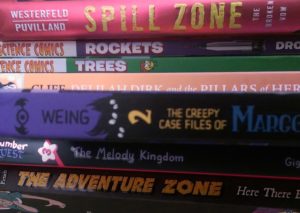

So I had Niven on the brain as I sat down to read three of the recent Science Comics which were kindly sent to me by the fine folks at :01 Books: Trees, Rockets, and Solar System. Let’s take ’em in order.

Trees, by Andy Hirsch (who contributed the volume on Dogs last year) was the book that I learned the most from; biology was never my strong suit, and I learned a great deal about the gross (and cell-sized, for that matter) anatomical structures of trees, expanding my vocabulary by quite a bit; given the age range the books are intended for, pronunciation guides in the text might have been useful (my wife, the trained biologist, corrected me on several occasions).

Hirsch starts with the general nature of the tree’s lifecycle, then carries the POV character (Acorn, who doesn’t want to plant himself, because trees are boring) through an exploration of the mechanics of tree growth, adaptation, reproduction, dispersal, forest-level impacts (on individual trees, entire species, and whole ecosystems), and ends up on the truly freaktabulous network of fungi that connects basically every tree in a vicinity to every other tree, allowing for energy and resource exchange, information transfer, and a whole lot more. By the time they’re all done, a tree looks no different, but a stand (or a copse, or perhaps a forest) starts to look an awful lot like a collective intelligence² and I am resolved to be nicer to trees in the future.

I didn’t learn as much from Rockets by Anne and Jerzy Drozd, but was impressed at the level of scientific detail included; this book is likely to be the one most challenging to the target audience, if only because it’s got math³. It also jumps around history a bunch, following different threads of the development of rockets (not unlike the seminal Connections series by James Burke, who knows a thing or two about rockets); it’s a nice addition at the back of the book that the history of rockets is laid out in chronological order, with references to pages in the story.

The story of rockets is conveyed by animals that have intersected rockets throughout history — a mechanical pigeon that flew in 400 BCE; a chicken, sheep, and duck that took the first artificial flight; Russian cosmodogs Belka and Strelka, and a pair of bears (a grizzly, who was involved in ejection seat development, and a polar bear … to talk about the Cold War). They all do a great job teaching the basics of physics (Newton’s laws, etc) and the fundamental paradox of rockets: to fly, you need fuel, but fuel adds weight, so you need more fuel to lift the fuel, so you need even more fuel to lift the first additional fuel…. And while I started this section by pointing out that I didn’t learn as much, I at least learned that Tsiolkovsky, the great theorist of rocketry, was largely self-taught because he was deaf and left school to take up residence at the Moscow State Library.

I was also pretty well-versed in the history of our Solar System, but Rosemary Mosco and Jon Chad did a nice job of bringing what could have been a rote recitation of facts-n-figures to life, electing to set up a framing story of a young girl home sick, her friend trying to stave off boredom, and pets recast as heroic explorers. There’s a snake with glasses, and a spacesuit pocket protector with pens in the pocket! There’s literally no way not to love that.

Also well done — expressing the scope and scale of things in space in ways that young readers can understand. The asteroid belt is largely empty space, contradicting every movie ever to show an asteroid belt. The immense size of our largest planets are well-explained, as well as some surprisingly small sizes. Did you know that Saturn’s rings are only about the height of a three story house? Or that Uranus smells like rotten eggs and cat pee? Or what the dance of a binary star system looks like? Or that Tycho Brahe got in a math fight and had his nose chopped off? That’s not a space fact, but it’s awesome nonetheless.

Mosco & Chad’s emphasis is not only on what we know, but how much we’ve discovered recently, and how much we don’t yet know … kids are going to absolutely be convinced that the world above (not to mention the one right outside the door) is one they can explore and discover themselves.

All three books are well situated for your tween-to-early-teen reader (with Rockets maybe on the upper end of the range and Solar System maybe on the lower end), and all come highly recommended. Solar System releases on 18 September, and the other two are available now.

Spam of the day:

Bettie Carbonara: Let us pick up the check =)

Sadly, not an offer to buy me dinner. Why are spammers obsessed with the costs of kitchen garbage disposal repair?_______________

¹ Rich Man, who was very poor and trying to make his fortune.² I also have the SC volume devoted to The Brain but haven’t read it yet; I might have gotten in a review four-fecta if I had.

³ All the way up to and including Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation; there’s also a math error that looks to be the result of a copy/paste mistake at the lettering stage. 1 kg at 1m/sec does not equal 0.5 newton, and hopefully it doesn’t confuse kid readers too much.