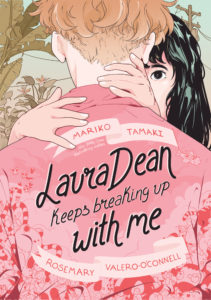

Fleen Book Corner: Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me

A few weeks before MoCCA Fest, the fine folks at :01 Books sent me uncorrected proof of Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me (words by Mariko Tamaki, pictures by Rosemary Valero-O’Connell) and I dove in. I held my review until closer to release date (which was, uh, two weeks ago) and then got caught up reporting on this year’s #ComicsCamp, so I’m late. But you know what? I got to read it a couple more times, so that’s okay. I’ve done my best to avoid spoilers — not much here you wouldn’t find on the back cover — but take care in any event.

My first readthrough caused me to think a lot about Kiss Number 8 by Colleen AF Venable and Ellen T Crenshaw, because they’re both about finding yourself, dealing with a shitty friend (and confronting the realization you might be the shitty friend), with LGBTQ identity to the fore. But LDKBUWM is less a parallel to KN8 and more a perpendicular. This is different time, a different place, a different reality in terms of LGBTQ freedoms. It’s not about finding yourself in the realization of sexuality or exiting a closet — most characters in LDKBUWM are either LGBTQ in some sense, or at least appears heteroflexible¹ — so if you take the coming out part of the teen story away, what do you get?

You get what was requested the Queers & Comics Conference: a queer comics character who’s bad. You get a character who can be a complete antagonist who happens to be queer, rather than a villain because they’re queer, or somebody that has to be presented as an exemplar of humanity to be a worthy enough queer to be included in the story.

Or if not a villain/bad in the traditional sense, at least a total dick.

Laura Dean is popular, hot, entitled, a mistreater of whoever isn’t in her favor at this instant (particularly her nominal girlfriend Freddie, who she keeps breaking up with) and a serial gaslighter; her go-to whenever called on her shitty behavior is Don’t be mad, making the subject of her mistreatment feel like they’re the one that’s at fault for overreacting. If only they’d been a better person, Laura Dean wouldn’t have had to act that way. Look what you made her do.

If Laura Dean were Loren Dean and presented as male, the story could be one step away from a cautionary after-school special about bad boyfriends that turn into abusers. As it is, she’s a user of people rather than an abuser, but if we check in on her in ten years I bet she’s got a TRO or two.

And as crappy a person as Laura Dean is, she makes those in her orbit worse, too. Freddie is neglectful of her friends, wrapped up in trying to get back into Laura Dean’s graces, knowing that she needs to make one of these breakups stick but half convincing herself that she can change enough that everything will be good in the future with Laura Dean. This is the finding yourself part of the story — deciding not how to present yourself as an identity, but deciding on how you choose to act.

Structurally, LDKBUWM is a little bit different; it doesn’t so much start as the reader begins paying attention to these characters at a certain point in time that’s really no more or less significant than any other. It’s arguably got a conclusion that it works towards, but really it just sort of fades out. The characters existed before page 1, they continue to exist after page 289, their stories continue and ebb and flow and branch and rejoin, like a river that we put our boat in at one particular place and pulled ashore again a few weeks later; we can see the extensions of the water upstream and downstream of the section we traversed and know that there’s more there.

Characters are revealed by small choices in their dialogue, but also in posture and visual habits. Freddie and her best friend Doodle both present as needing affection and attention, but they go about it in different ways. Freddie’s all public gestures and reactions, where Doodle is made of quiet implication. I spent my first read thinking that Doodle’s somewhere on the autism spectrum but have ultimately decided that she isn’t — but she was raised by a single parent who is. Her affect is of somebody that is learning to be demonstrative, having lacked the example of it at home. None of this is stated, and all of it may be completely off base, but it’s how the characters read to me … and it’s been a long while since characters on a page have left me with such distinct impressions of who they are by subtle implication.

That’s equally down to Tamaki’s plotting and dialogue and to the visuals, which let’s discuss. I’ve been talking up Rosemary Valero-O’Connell for about three years since I first met her. I said at the time that her minis reflected an unusually strong sense of page composition and design, and that her characters reminded me of two veteran manga creators whose work I love. Both have improved in the intervening time, especially her faces. Freddie has bits of Terry Moore’s Francine Peters in her big, expressive face, and Doodle says more with a raised eyebrow than a page of dialogue could contain². Crucially, and it’s the first time I’ve ever noticed this, Valero-O’Connell’s faces retain their expressiveness in 360 degree rotation; with remarkably few lines, there’s a shifting in the shape and weight of mouth, cheeks, eyebrows, and the entire skull shifts to convey mood.

She’s not afraid to have people speaking over their shoulder, and let the listener who’s facing us have the reaction; it’s astonishingly strong work. Plus, she does this one bit where a jerk jock is all homophobic at supporting character Buddy: we never see his face but can tell from the tilt of his head, the slump of his shoulders, the refusal to look at the gym coach who’s dressing him down, exactly what expression he’s wearing. Yeah, it’s our brains filling in what we can’t see, but it’s also the case that Jerkboy has the same blonde undercut as Laura Dean, and we’ve seen enough of her shitty girlfriend entitled smarm to fill in that detail. The reader, on an instinctual level (it took me four or five readthroughs to realize it), has been promoted to full partner in the visuals of the story.

And those visuals are lush. The characters — not just the named ones that we get to know, but all the backgrounders going through their own stories that we don’t get to eavesdrop on — are all unique. Skin color, modes of dress, hairstyle, size and shape — all of them are varied, giving the sense of a public school in a place that’s truly diverse (Berkeley, California), as opposed to TV or movies³ where a “diverse, random” crowd is 70% male and 70% white and all “Hollywood average” in appearance.

It’s not just people who’ve been on the receiving end of a bad partner in a relationship that will feel seen reading LDKBUWM, it’s just about everybody — there in the background, each character drawn with the same care and respect as the starring and supporting players. Someday, Tamaki will write or Valero-O’Connell will illustrate some of those stories, and we’ll see Freddie or Doodle or Laura Dean pass by in the background.

Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me is a stellar achievement in comics, and is the one to beat in my private list of best books of 2019. You can find it wherever books are sold, and carries my highest recommendation for the teen-and-up in your life.

Spam of the day:

You will be glad to know [spammer] which belongs to Bing and Yahoo, as one of the largest pools of advertisers in the world, they pay more to buy your traffic.

Ooooh! You belong to Bing and Yahoo! Know who else belongs to — that is to say, is findable via — Bing and Yahoo? Everybody.

_______________

¹ Crowd scenes feature lots of seeming same-sex or gender ambiguous couples, which may be part of the script or may be a choice on Valero-O’Connell’s part.

² I’m reminded of longtime NPR Morning Edition host Bob Edwards, who could vocally lift an eyebrow over the radio with a single, arch syllable — Oh? — when interviewing some political powerbroker who was clearly lying.

³ Or too many comics, sad to say.

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.