Fleen Book Corner: China Endures

China is old, perhaps oldest of human endeavours; there is a cave system outside what is now Beijing where people lived for some 200,000 years, until the mass of the ash from their own fires finally displaced them. The first dynasties were established thousands of years before the start of the common era, and since that time one script has united different people and languages into the idea of “China”.

They knew of and traded with imperial Rome and the great Islamic empires; in the 1400s Admiral Zheng He definitely led fleets as far as Africa and possibly east across the Pacific to California, sixty years before Columbus led three tiny ships across the much-smaller Atlantic. Every idea, story, parable, intrigue, religion, philosophy, and thought that’s been had in the vast swathe of human history, probably it’s been had first (or independently, or in a parallel form) in China.

Skip forward to 110 or so years ago and the last of the imperial dynasties finds itself in a very different world: the Western powers have semi-colonized a vastly weakened China. Although they recognize the government of the empress, they have carved out for themselves concessions and enclaves complete with soldiers and extraterritoriality. They are essentially able to take as they wish from China, force any trade or behavior or law upon her people, and are immune to any repercussions.

This is perhaps not a long-term viable position in a country of (at the time) 400 million people with a weak central government that cannot order them to tolerate the outsiders, and a vast cultural memory of great emperors, generals, gods, and heroes. It is a time of upheaval and a people fed up enough with the situation that they are willing to fight with fists and spears against repeating rifles and artillery pieces; it is a time of cruelty and bravery and stupidity and honor and massacre and righteousness and vengeance and mysticism and blood, so much blood.

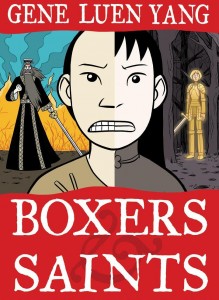

It is the Boxer Rebellion, and Gene Luen Yang has found in this time of tumult the perfect mixture of the topics have have suffused his prior work: what it means to be Chinese in the historical sense and the modern; what it means to be Christian, in living up to that philosophy’s gentlest ideals, and as a crusader. He has at last surpassed American Born Chinese — an astonishingly adept and powerful work — and produced an even more powerful masterpiece, in the form of Boxers and Saints.

I have been reading both books (more than 500 pages of comics) repeatedly since the good folk at :01 Books provided me with review copies in June, and I would like to share some thoughts with you now, on the eve of their general release tomorrow. For those that don’t know how these things go, consider the remainder of this post to be rife with spoilers.

1898; two people meet although they don’t know they’re on a collision course: Four-Girl doesn’t have a name of her own and is despised by her grandfather, who rules the family. Little Bao has a happy enough life with his father, Big Brother, and Second Brother, especially in Spring when there are markets and festivals and opera performances. They meet, although neither will truly recollect it.

Their lives will intertwine as they fall in opposite tracks of China’s interactions with foreigners: Little Bao sees a foreign priest meting out his own views of justice in a dispute he cannot properly comprehend; he is protected by opportunistic thugs who latch onto the priest not out of belief, but for the protection they derive from his status. Those that latch onto the westerners prey upon their fellow Chinese, exploiting the village folk to perhaps a greater degree than the westerners themselves.

Meanwhile, Four-Girl pulls further and further away from her family and into the orbit of the same priest, initially because she gets food, eventually because of something resembling ecstatic visions of Jeanne d’Arc. Today they’d call Jeanne schizophrenic and Four-Girl (or Vibiana, as she is baptised) may have the same touch of mental illness … but nobody told her the story of Jeanne before she had her visions and conversations with the martyred girl her own age. Her understanding of Christianity is naive and unsophisticated, but when you’re in the business of collecting as many souls as possible, you perhaps aren’t too picky about those you convert.

Eventually, the depredations become too much; here and there peasants band together to defend themselves against the westerners and opportunists, and then to revenge themselves for particular hurts, and then to drive them away entirely. Eventually, Vibiana seeks out the relative stability of a Christian enclave/orphanage, although her life isn’t much better than it was with her family and she asks too many questions; Jeanne’s answers are cryptic, and the priest has little time for them.

Little Bao may be no less removed from reality in his visions than Vibiana, though; he and his brothers — and friends, and eventually many others — burn sacred charms and ingest the ashes and become the literal personifications of the gods and heroes of classical China. Their appearance changes, great winds appear, they are invincible in battle … at least at first. They have the blessing of the empress, as they rampage across the countryside, killing and driving out every western devil and secondary devil (convert) they find. Here Little Bao and Vibiana meet again and although Vibiana decided to follow her visions of Jeanne and become a holy warrior herself, she got it into her head to begin training mere hours before Little Bao’s army descended upon her village. Her defiance would not survive the day.

The conflation of supernatural and natural have settled down at this point; when without the element of surprise, when not facing firearms, in the throes of their shared visions, Little Bao and his brother-disciples could actually be those gods and heroes and monsters; when they fall to bullets and explosions, their corpses are decidedly ordinary.

With each fight, each new and larger village, town, city, and eventually into the streets of the capital, the visions and presence of the gods lasts less time; the colors, so rich in the shades of laquerware and opera costumes, revert to the dusty ochres of peasant garb all the quicker. Fantasy retreats and teality asserts itself more forcefully, escalating to the utter defeat of the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fist in the streets of Peking.

But was it all reality? Vibiana is dead, her story ending when she and Little Bao met; he didn’t want to kill her, she didn’t want to recant, and in the struggle between one person of belief and one person with a sword, the outcome is pretty much pre-ordained. That’s how I died she narrates — but from where? And how did she learn of other things that were happening elsewhere as she died, incorporating them into her story? To what degree did the visions lead her to teach a Christian prayer to Little Bao, which he used to convince vengeful Europeans that he was a convert himself and escape the mopping-up in Peking? Little Bao’s visions died away as he and Second Brother limped out of the city, faced with a reality — a modernity — where ancient beliefs can’t assert themselves. But Vibiana’s beliefs are ancient as well, and served to protect at least one rebel Fist.

The story isn’t so simplistic to present this as a supercessionistic viewpoint, but Yang has previously melded together his Chinese heritage and his Catholic belief system, finding parallels and intersections between the Gospels and the Journey to the West. The parallel nature of belief and madness that Little Bao and Vibiana experience can only result in death … until Little Bao accepts a small measure of Vibiana’s belief, even just for a moment, and the synthesis produced something that could survive.

After all, every idea, story, parable, intrigue, religion, philosophy, and thought that’s been had in the vast swathe of human history, probably it’s been had first (or independently, or in a parallel form) in China. Only by joining China and not-China results in a thought strong enough to survive the clash of the ancient and the modern.

Boxers and Saints are powerful, affecting, gorgeously drawn, complex, and require multiple re-readings. I’ll be teasing out new meanings for years to come. The only thing that I won’t eventually be able to do is read them again for the first time which is a shame, as I find myself wondering how much the story changes if they’re read not as Boxers and then Saints, but the other way around. Vibiana’s story fills in the gaps of Little Bao’s when Boxers is read first; I wonder if the converse is true when the order is reversed.

Probably: Boxers and Saints are stories where almost nobody comes off well; nearly everybody is variously overly dogmatic, viciously orthodox, adopting belief systems for the wrong reasons, and trying to spread those beliefs as an act of hegemony verging on warfare. The priest particularly bad — self-righteous, self-aggrandizing, judgmental, iconoclastic¹ and generally a prick. Had he walked in life with the humbleness that he achieved in death … well, everything would have happened exactly the same, because he’d be one non-jerk foreign devil in all of China. But had all the foreigners that he represents walked more humbly, as teachers rather than crusaders, much misery may have been avoided.

Or maybe not, as many of the priest’s shortcomings were already there in China, particularly the fear, distrust, and denigration of women that he shared with Four-Girl’s grandfather. Reversing the order won’t shift either group in terms of the hurts it believed it suffered as the aggrieved party, nor lessen the crimes that each committed. The two don’t exist in a linear relationship of one first and the other second; they swirl into each other, each preceding and following the other, forming a circle of action and reaction.

Boxers and Saints are required reading. If you’re going to read either, be sure to read both. Then set them aside, go learn some about China — there’s always more to learn about China — and read them again, and again. They’re that important. They’re that good.

_______________

¹ Literally, at the start of Boxers.

[…] that review of Boxers and Saints yesterday took a lot out of me, and preempted some news that would have been timely yesterday. Let’s […]

By Fleen: Try Our Thick, Creamy Shakes » Catching Up on 09.10.13 5:13 pm

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.