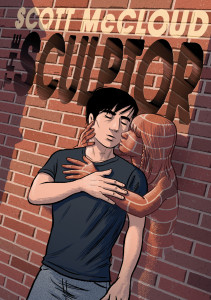

Fleen Book Corner: The Sculptor

I have been taking my time getting around to this review; both because writing it six weeks ago (when Gina Gagliano at :01 Books very kindly sent me an advanced reader’s edition) would have been too early to be relevant — The Sculptor doesn’t release for another week — and because, as I said at the time:

I’m unable to produce one right now because I am not able to stop experiencing this story, to step back to see it in detail and in the whole, to think. It is, at the moment, a wholly emotional experience.

The thing is, that really hasn’t changed much for me, but at least we’re closer to the release date so what the hell. Let’s talk about Scott McCloud’s latest book, his first work of fiction since 1998, and what is likely to be the best work of graphic fiction of 2015. For once, there will not be a large number of spoilers; weirdly enough, the twists and turns of the story are not the centerpiece of the experience.

I feel a little guilty having read The Sculptor, and suspected that I would ever since I saw McCloud and his family read excerpts at last summer’s San Diego Comic Con. The relationship between the titular sculptor (David) and his Beatrice figure¹ (Meg) is unambiguously, nakedly, unashamedly inspired by McCloud’s own meeting and early relationship with his wife of 27 years (happy anniversary!), Ivy; I feel like I’ve been eavesdropping on the parts of their personal history that only they know.

Except for the part where Scott would have a deal with Death and a very limited lifespan and a might-have-been-great/presently-not-so-much career and mad go-for-broke ideas about how to express everything inside him, and the part where Ivy would be the centerpiece of an eccentric community of once-broken, now-healing people and suffers from a bipolar cycle that causes to push everybody around her away on occasion.

Except-except for the parts where all that is true — Scott did have a critically-acclaimed but only modestly successful career and no great name recognition when he embarked on Understanding Comics — a mad idea if ever there was one. And Ivy is the centerpiece of a community of wildly creative people, and you can ask anybody — many of them may have come into the McCloudian orbit because of Scott’s work, but people stay because of Ivy.

So how many of the little intimacies between Meg and David are fictional and how many come right from the experience of Ivy and Scott? Where are the truths and where are stories? On the surface, they’re all stories, but in their heart I think they’re all true.

And that thought — surface versus heart — put me in mind of a key proposition from Understanding Comics and made me realize that there is more McCloud-specific history in The Sculptor than the relationship of David and Meg. Because The Sculptor is not just the story of how David found his means of expression, it’s also McCloud’s.

I’ll be perfectly honest: the beginning of The Sculptor didn’t wow me; the story was perfectly acceptable, but acceptable is not what I’d expected from McCloud. The story beats were exactly where I knew they would be, the progression entirely by the numbers, nothing novel or amazing. But then, slowly, almost imperceptibly, McCloud began to peel back that surface of story and play with the elements underneath and I realized that what I was reading was a retelling of something McCloud had written before:

The Sculptor is chapter seven, The Six Steps, of Understanding Comics.

Surface, you’ll recall, is the part of art we see first — the superficial part, separate from inspiration; below it lies the realm of Craft, where McCloud’s skill starts to be applied to both story and visual elements. It first struck me in the crowd scenes, where every one of dozens — hundreds! — of human figures was rendered fully. Reading back I noticed people in the background weren’t just static, but were interacting with each other, arguing, living full lives. McCloud’s mentioned how he worked at a massive size when drawing The Sculptor on his Cintiq specifically so he could include all those background day-players in the detail they deserved.

This lead to my realization of the next layer down — Structure — where I realized that not only did all those people get drawn, but they all had their own stories, occurring at the same time as David’s, each of them the star of another 400, 500 page story, intersecting with this one only in the most peripheral of ways. Peeling further down, I could sense the way McCloud using the story to express his Idiom, his thoughts on the nature of comics, what they can represent, how they can teach like no other medium. Being caught up in this discovery, I found myself surprised by how the story — which I’d initially thought a bit obvious and a bit pokey — had looped on itself, shifted into unforeseen directions, and was now accelerating at an alarming pace.

Where things had started out languid, as David’s time gets short and the number of pages gets low, the story speeds up. Not a line of dialogue, not a gesture exists to set stage or provide color — they now all serve solely to propel the story in a way that could only be accomplished via the Form of comics. No other medium gives the creator so much control over the perception of time; I’m convinced that McCloud consistently and subtly reduced the spacing between panels by fractions of a millimeter per page² in order to speed up the perception of time in a gradual fashion from the start to the climax.

And what a climax, as the Idea become apparent. This wasn’t David’s story, or even McCloud’s. It was always a presentation of a philosophical question, bigger than any of us: What does it mean to create, and how do we deal with the compulsion to do so? Family, discovery, life, creation, loss, irritation, coincidence, tragedy, hope, betrayal, love, celebration, ice cream, secrets, death: McCloud wants us to know that they are all capital-A Art.

He may have spent more than twenty years telling us how all of these tie up in the package known as Comics, but now he’s done telling and decided to show us instead. Three books tickled your objective mind and lead you to understand, reinvent, make comics; now he’s nudging your emotional mind to feel your way through those ideas in service to a story that feels real like a rapidly fading dream feels realer than anything else. It’s a heady experience, and one that required every single absorbed lesson and evolved theory that his career has allowed. It’s a love letter to everything that Scott McCloud holds dear, and needs to be read by everybody that loves comics.

The Sculptor will be available at booksellers everywhere on Tuesday, 3 February 2015.

________________

¹ Although she’s a mix of Dante’s Beatrice and Shakespeare’s.

² Not that I have measured; if it turns out he didn’t and it was all in my head, I don’t want to know. The story I’ve told myself is its own truth.

[…] ¹ My review here; it’s a masterpiece and I’ll be buying a copy tomorrow, since apparently there’s […]

By Fleen: Try Our Thick, Creamy Shakes » Busy Day on 02.02.15 12:50 pm

[…] comes out, and all indications are that people are eager for it. My feelings on the book are on the record, and I am looking forward to McCloud’s talk this evening in New York City. But could I […]

By Fleen: Try Our Thick, Creamy Shakes » Goodbye And Hello on 02.03.15 12:34 pm

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.