Today I Am A Sad Panda … Not Really

It appears that I got the release date wrong for Achewood Volume 2. Although Things From Another World (closely associated, possibly owned by the same people as publisher Dark Horse) lists the publication date as 2 September (yesterday!), it was not at my local shop. Dropping by Borders, they have the book listed for pre-order for the 16th, and Amazon.

Bottom line, looks like I won’t get Worst Song, Played on Ugliest Guitar for another two – three weeks. Even more disturbing, as I was just typing this, my Freudian subconscious invented a book called Worst Song, Played on Ugliest Guigar (I swear to God this actually happened) and I do not want to know what that means.

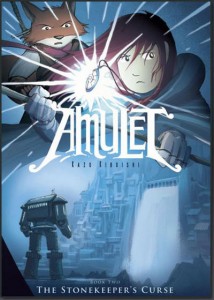

But despite these trials which might reasonably be expected to break the spirit of any man, I am in a tremendously good mood today, because my local shop did have a copy of Kazu Kibuishi‘s just-released Amulet Book Two: The Stonekeeper’s Curse and oh boy is it good.

For starters, don’t sit down with this book unless you have a lot of time free; it clocks in at more than 200 gorgeously-illustrated, beautifully thick pages (I’m a sucker for the physicality of books — and when a compact trim size like this is dense and heavy in the hands, I’m over the moon), but may well be the fastest 200+ page read ever. There’s no pausing here, as the story forces you from beginning to end at a brisk pace, with no time wasted (but with the narrative not being rushed either).

Then comes the compulsive re-reading, as this story draws you back and demands that you go over it again — first in individual pieces, then in large chunks, then from front-to-back again. I’m on pass #4 and anticipate at least a dozen before I can put it to the side. If you do not wish to have elements of plot revealed to you, stop reading now and call this review a five-star rave. For those willing to risk it, spoilers ahoy.

In my review of the previous Amulet volume (nearly two years ago — stories this good take time to produce), I compared Kibuishi to Hayao Miyazaki, noting some mostly-visual aspects of the story:

[C]haracters with open, simple, but incredibly expressive faces; the choice of the young girl (not quite ready to be a woman) as the protagonist; the stylish, otherworldly, and lovingly-crafted flying machines; the landscapes and critters that clearly come from a dream world that isn’t all rainbows and lollipops.

This time around, the Miyazaki vibe is even stronger, and with more time to get to know the characters, it’s more about the type of story that Miyazaki tells, and the type of people he talks about. Allow me to digress a moment.

If there’s one near-universal in how our global culture treats stories, it’s this: little girls want to be princesses. Disney’s built an empire on the fairy tale of pretty gowns, the handsome prince who doesn’t do very much (but swooping in at the end makes everything suddenly okay), then the wedding and happily ever after. Below the surface, it’s all about teaching girls that the best they can aspire to is to get married and start a family.

But you know what? Little girls are smarter than that, and some storytellers know it. Miyazaki gives us princesses, sure, but these princesses live in a world where the concerns aren’t handsome princes and pretty things — they’re making sure that everybody you love lives to the end of the day and dealing with those that would threaten them. These princesses are protectors and preservers that just want to keep home safe, and Kibuishi knows how powerful that motivation can be.

Emily, the Stonekeeper of the title (although we find out now that she’s just one of many stonekeepers), is concerned with nothing more than saving her mother (grievously poisoned in the first book), and then getting herself, mom, and brother the hell out of this magical world and back home where they belong. The whispers of the amulet that she can have anything she wants — happily ever after — are shoved away like the false promise they are. But when it becomes apparent that “home” and “family” are more tied to this new world than she thought, Emily rapidly grows into accepting the responsibilities of a too-soon adulthood.

The new book brings other new elements to the story; whereas before Emily was given mechanical constructs to serve and protect her, we are now introduced to a warrior born-and-bred to teach Emily how to control her power and protect all the world (this relationship with Emily is reminiscent of that between Nausicaä and Lord Yupa). We meet the people of that world (laboring under a curse that turns them, slowly at first, into animals — and not all cute & cuddly ones), who themselves want nothing more than for their oppressors to go away, and have built a resistance to make it happen. We meet the wise teachers of that resistance, the ultimate philosophers, able to predict and prophesise, but literally helpless in the face of their enemies.

And we meet The Stone, that thing of power that offers great ability to protect and nurture, but also to corrupt and threaten.

These stones have their own voices and desires, and we learn that years ago, four young stonekeepers gave into their stones and became monstrous creatures; one survived the defeat and imprisonment and attempts to free him from his stone’s influence, and he is now the Elf King that threatens all the world. This nameless, faceless king appears to wears a mask that resembles his stone, a total submission to its will, literally hiding behind it. On a later read, I began to believe that perhaps the stone has so incorporated itself into the king’s being that it has grown and merged with him, and now literally forms the face which the king presents to the world.

This is pretty heady stuff for what’s nominally a young readers book — either submitting to evil and pretending it’s not really you as you hide, or so embracing it that you show it to all that look upon you. The seductive nature of power is presented clearly, without any of the gradual temptation that usually accompanies such stories — in its first communications with Emily, the stone promises power and all her desires, if only she gives in to its control. These are no gradual lessons about “seeing” lightsabre practice drones even with the blast-shield in place, to be gradually supplemented by whispers in dark places. From the beginning, the offer is there on the table: Do not resist. Submit and have all you wish. Emily knew from the beginning that was a fool’s bargain, and now she knows the stakes.

But although Emily is the star of the book, there’s also a new and expanded role for her brother. Say what you want about the lessons that girls are taught, boys from the beginning imagine themselves into stories where they’re important and powerful and have swashbuckling adventures, lessons or no. And even when you find out that you are important and powerful and it turns out to be not really what you wanted at all, on some level it’s a comfortable place.

No less than Emily, Navin wants to get home safe with Mom, but if you give a pre-teen boy a lesson in how to drive a giant house mecha, he’s going to take to it like he’s been preparing for it his whole life. This is because every time he’s daydreamed in class, or when he was supposed to be doing chores, or bored, he was preparing himself to drive a giant house mecha. In fact, that giant house mecha is the 21st century equivalent of Chekov’s gun: If you show a boy in control of a giant house mecha in Act I, he had better beat the snot out of a giant monster with awesome rocket fist punching by Act III.

And that’s before the boy in question has even properly absorbed the fact that his sister may be one of the magical protectors of this world, and he is by prophecy the commander of an army of ninja animals (of course there are ninja animals — ninjas are universal), including the grossest bugs and creepy-crawlies. That sound you just heard is a nation of eight year old boys, whose minds are furiously imagining the possibilities. There are plenty of places for young readers to get lost in the action — think of it as dessert after absorbing those lessons on evil and power.

Mind you, I’ve had the book for less than 24 hours, and it’s not yet comprehensively worked its way down into my psyche. Ordinarily, a story with so much further exploration, I’d be waiting to talk about it, but not this time. This time, I tell everybody how good it is from the very beginning, because the possibility that a single person might way a single day to pick this book up for themselves because they hadn’t read a recommendation yet? That’s a small tragedy right there. If you’re in America, it’s about two cents a page, which might well qualify as the bargain of the century. Go read The Stonekeeper’s Curse. Do it today, and you’ll thank me tomorrow.

I’m a happy panda…just got the email from Amazon announcing that my Achewood vol 2 has just shipped! Should be here in a couple of days…

By Steve G on 09.06.09 5:26 pm

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.