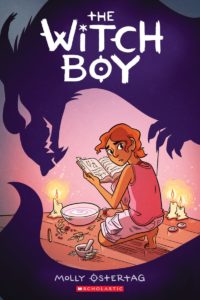

Fleen Book Corner: The Witch Boy

I finally got the chance over the weekend to pick up a copy of The Witch Boy by Molly Ostertag; given that it released nearly two weeks ago, this was long overdue. Short version: you want to read this book which is beautifully illustrated, clever and subtle in its message, and a cracking good read; more importantly, you probably know somebody in the target age range (call it 8-12) that desperately needs to read this book. Longer version is below, with the requisite warning that spoilers abound.

Aster has the same problems as any other just-teen boy — cousins that make fun of him, a family that doesn’t understand him, expectations that he beats himself up for not fulfilling, or even feeling that he can fulfill. Then again, he’s got some problems that other just-teen boys don’t — three generations of his family, 20 or more people, all live together in a big house that’s somewhere between isolated and quasireligious compound.

There are rules in the family, too, some of which would be downright sinister in a slightly different story (don’t talk to strangers, don’t leave the property, there are evil things away from this place of safety that want to destroy you), and a great big one that dominates the story:

The family (and others like it, scattered around the world) has magic. Girls are witches. Boy are shapeshifters. Acting outside those roles is forbidden and dangerous.

Come to think of it, the blind faith in gender roles is still sinister, even though it comes from a place that’s more benign that a lot of real-world implementations¹. Aster understands, and he wants to fit in — he begs unseen fates to let him fit into his assigned role — but the truth inside him is undeniable. Shapeshifting doesn’t work for him, and he’s drawn to witchery.

Nobody understands, not his parents, his sister, his cousins, aunts and uncles … although Grandmother surprisingly doesn’t berate him, despite knowing more than any the danger in fighting the system. If you’re going to be playing with witchery, she says while correcting his pronunciation, at least get it right.

The only person he can confide it should think him even crazier than his family does — wandering out past the wards and guardian spells into suburbia, he meets Charlie: nonmagical, dreads on her head, denied participation on sports teams because they don’t let girls on them. She catches him doing magic, he confesses his misgivings, she tells him he should be who he knows himself to be. He’s a witch, and hers is the only encouragement he gets.

Good thing too, because one of those dangerous things wanting to destroy the family starts stealing away Aster’s cousins as they try to improve their shapeshifting. It whispers in their ears that it will make them powerful, let them defeat all those that have wronged them; Aster should be easy prey for temptation, but the tempter can only offer what Aster’s not interested in: mastery of shifting. Ultimately, it’s Aster’s delving into forbidden areas (scrying, healing, binding) that saves his cousins and unmasks the danger preying on his family. It takes some time (and a rather surprising remonstration from Grandmother) to set his family on the path of acceptance.

But — and I think this is the most important part of Ostertag’s message — there’s tension still there when Aster admits to Charlie, Mom and Dad don’t really get it, but … I don’t know, they haven’t kicked me out or anything. It’s a shock to their worldview and they don’t understand, but they love him. The rules are changing more quickly than anybody knows what to do with, but Grandmother’s word is I think we have much to learn from each other. And Aster decides that there are some rules you have to figure out for yourself.

Aster doesn’t get happily ever after because his life isn’t a fairy tale. It all worked out is messier, but ultimately more achievable. There’s a lot of readers of The Witch Boy (young and old) that need to be reminded that achievable changes and the path of acceptance and figuring out rules for yourself are things that can happen. Not usually as quickly as for Aster, but they can. And if their families aren’t as accepting as Aster’s, then deciding who gets to be their family is one of those rules you figure out for yourself.

Aster is people, Ostertag is telling us. Grandmother, who’s more than solely a witch and never admitted it before, is people. The rest of the family, coming around on their lifetimes of habit, are people. Charlie is people. Even the adversary is people, or was before he fell and rejected everybody that wasn’t him². The Witch Boy tells us unambiguously that anybody that tells you that you aren’t people, they need to come around.

In the meantime, you can come sit here with us. We know you’re people.

Spam of the day:

Black Friday racking up debt?

This doesn’t work until after Black Friday. You’re ten days early, scammers.

_______________

¹ Rather than being based on ancient dictates and the subjugation of women, the customs of gender roles is reinforced by a recent, living memory disaster of what happened when Grandmother’s twin brother tried to be a witch. Think fallen Jedi in thrall to the Dark Side.

² Or perhaps, was rejected by everybody around him, leading to the fall. There’s plenty of blame to go around there, even among the good folk of the family.

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.