Fleen Book Corner: Knife’s Edge

Here’s what I wrote eleven months back regarding Compass South (book one of the Four Points series, words by Hope Larson and pictures by Rebecca Mock):

Much has been made of the similarity of comics and movies, but Compass South makes me think that the stage is a better comparison. The stock characters of comics — mysterious playboy/nighttime hero, the youthful ward, the alien with powers beyond those of mortal men, the angsty teen thrust into responsibility — are just as recognizable as the stock characters of the commedia dell’arte — the doomed lovers, the evil prince, the hidden twins, the unscrupulous businessman, the unrepentant villain, and the jolly comic relief — that Shakespeare appropriated and made central to the theatrical world. Larson’s combined the two traditions, and it makes for a cracking story that enriches both.

There was a footnote, too, where I commented on another influence:

[I]n addition to comics and theater, there’s the literature of the time. More than one character in Compass South is more than a little Dickensian, including a guy who’s very possible Fagin’s second cousin twice removed (in temperament, if not not actual relation).

I think I was onto something there; Knife’s Edge (book two of the Four Points series¹, words still by Larson, pictures still by Mock) switches from the Shakespearean mode of shifting between competing protagonists to the Dickensian mode of a primary protagonist with supporting characters of varying importance in orbit.

In part that’s because of where we are in the story (which Larson efficiently recaps, oh and obviously — spoilers ahoy): we’re down one set of twins, we’ve found one long-lost father, and the villain is already established. Not having so many balls to juggle, Larson can focus the story more narrowly, and she’s chosen to put it squarely on the distaff Dodge, Cleo.

(This is where the Dickensian analogy fails somewhat — Pip and Oliver can suffer travails and come out happily prosperous; Little Nell is doomed to die of consumption.)

Alex has it easy — he can declare he’s going to be a tall ship captain and have a shot at making it come true. He can indulge in the relatively simple, linear path that male heroes get to follow:

- Long-lost father found? Check!

- Villain identified? Check!

- Clear and reasonably achievable (if challenging) goal to ensure lifelong success? Check!

- Sudden revelation that there’s a long-lost mother as well? Don’t care!

Cleo has to navigate the much more labyrinthine path that she’s afforded in 1860: she’s expected to take care of her semi-invalid father and help out in the ship’s galley. No sailcraft for her, and as soon as it’s discovered she’s convinced the captain to give her swordfighting lessons², that’s stopped because it’s inappropriate.

But here’s the thing — she’s got more imagination than Alex; she sees the many possibilities that aren’t laid straight out, living in a world with greys instead of pure blacks and whites. Alex isn’t interested in learning about their piratical heritage, but it doesn’t quench Cleo’s wanting to know who and why.

That ability to think laterally proves critical in the final defeat of the villainous Felix; Cleo can imagine how clever her never-met mother would be, where Alex only sees the situation directly in front of him. And if finding answers — not treasure, not glory, answers — means declaring truce with the enemy³, then that’s what she’s going to do.

The internal character of Cleo and Alex is found throughout Mock’s gorgeous illustrations; it’s not easy making 12 year old twins look different, but she does. Cleo and Alex wear slightly different clothing, but it’s subtler things that let you know who they are. They part their hair on different sides; they have different postures; Alex’s gaze more frequently angles slightly down, while Cleo’s is up.

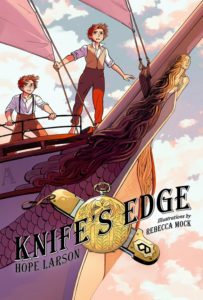

But the real difference is on the gorgeous cover. Alex is solidly braced on the railing, in his environment, but a little behind Cleo and subconsciously following her lead; she’s looking out to the horizon, posed like she’s ready to leap forward. The sailor’s world may not wholly accept her, so she’s looking for the place that will. That vision makes her susceptible to temptation and corruption, but brings with it the strength to achieve redemption.

By the end of the story, she’s ever so slightly taller than Alex, too — grown sooner than the boy that’s got it all figured out. And if Cleo (and Alex, and Father) doesn’t quite get the ending she figured, she’s smart enough to know that the happy outcome can be more subtle than a 12 year old with a head full of imaginings would initially suspect — finding her place in the world is a smaller victory than she’d expected when she set out from Manhattan’s slums, but a meaningful one.

Give both Knife’s Edge and Compass South to anybody that loves a good story of adventure, but particularly the pre-teen that needs reminding girls have awesome adventures too.

Spam of the day:

20 Summer Life Hacks To Get You Through The Hot Season

If this reads anything other than avoid pants, I ain’t interested.

_______________

¹ Alas, it appears there will not be a third or fourth book (which you’d think would be a natural with a series title like Four Points).

² She has a well-founded fear of what a particularly nasty pirate has in mind for her family, and doesn’t want to meet a potentially bad fate passively.

³ No matter how obviously that’s going to blow up.

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.