Fleen Book Corner: San Diego And Silences

As a professional communicator, a colleague once opined to me, the most important tool you have at your disposal is silence. He turned out to be kind of a weird guy, but he had been an announcer for the CBC in his youth, so I imagine he had that part right. It fit with my own experiences in radio oh so long ago, and was almost word-for-word something that Ira Glass said about a year later:

I like Harry Shearer, who does a show on KCRW in Santa Monica that’s syndicated to some stations around the country. Listening to his show taught me that it’s okay to pause however fucking long you want to in the middle of a sentence on the air.

So — silences are good; keep that in mind as I talk about three books today, which have in common a couple of things:

- Copies were gifted to me by the respective authors on the floor of SDCC

- Each of them approaches its story with a unique appreciation for silence

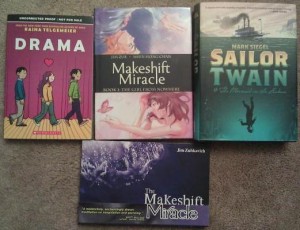

We’ll start with DRAMA by Raina Telgemeier, read in an uncorrected proof edition, and available 1 September. Like her earlier, autobiographical Smile, DRAMA takes place in middle school, and Telgemeier’s ear for the early teenage years — the rhythms of speech patterns, the small dramas that loom so large within the framing story of a drama club’s spring production — is as sharp as ever. Callie, Jesse, Justin, Liz, and all the others aren’t facsimiles of 7th- and 8th-graders, they’re living, breathing, scheming, hurting, striving, entirely alive people that just so happen to have originated somewhere in Telgemeier’s imagination.

She uses silences in all the expected ways — montage, reaction, actions that don’t feature anybody talking — but also as gutters. The gutters, Scott McCloud taught us, are where the reader has control of the story and determines what happens that isn’t being explicitly shown. The difference here is the actions are being shown (without words) at big emotional beats; where one panel would have more than adequately gotten across the mood of the story, flipping the page and finding two, three, four more panels, spread across as many as two pages, serves as an extended moment of audience interaction.

Callie is {humiliated | lost | abandoned | embarrassed | other} — choose from your own experience, the mood that resonates with the reader has no choice but to build over the time it takes to traverse all of those “extra” panels. Those silences are uncomfortable, not because we’re told they are, but because Telgemeier makes us remember every time we’ve ever been in those situations. Bravo.

By contrast, Makeshift Miracle Book 1: The Girl From Nowhere (available now, although the comics in this volume only finished online three days ago) by Jim Zub (Mr Zubkavich, if you’re nasty) uses silence as a counterpoint to internal monologue. Some of you may have read about Colby Reynolds and the mystery girl, Iris, in Zub’s original treatment, The Makeshift Miracle, collected in book form in 2006; back then, Zub handled both writing and art chores, and while Zub would be the first to say that the new, full-color art by Shun Hong Chan is an improvement, I always thought that the original made for an intimate, singular POV in the story.

But this is a different story, not just different art. Story beats have been rearranged, the narrations (from the explicit perspective of a diary written after the fact) have largely been replaced with an in-the-moment reactive monologue. Most importantly, the story has been given much more room, by a factor of 50-100%, with single pages being replaced by two, three, or more where necessary. Colby doesn’t have that much more to say, thus — silences, and plenty of them. The additional room gives the ability to show more and tell less, making the story less Let me tell you what happened to me and more Come along and see what’s going on in my life.

The otherworldly, mysterious interactions of Colby and Iris give the story the space to breathe. It’s not just an exercise in decompressed storytelling, it’s taking the opportunity to stop and smell the weirdness that the characters otherwise would have been too nonchalant about. If you have a copy of the earlier The Makeshift Miracle, don’t look at the new edition (which isn’t complete, in any event) as a replacement; these are the same story, but different treatments that deserve to be evaluated on their own merits.

Finally, Sailor Twain, or, The Mermaid in the Hudson (collecting the now-completed webcomic, and generally available 2 October) by Mark Siegel, also known as the editorial director of :01 Books (which, as previously noted, is pound-for-pound the most celebrated graphic novel publisher in the world). Here, along the Hudson River from Manhattan to Albany, amid Gilded Age wealth and decadence, silence is almost a force of nature.

Things that should be noisy — violent storms, enormous side-wheeler steamships, Civil War battlefields — are rendered with barely a sound effect or indication of shouting. The effect is striking, particularly in a story that emphasizes the dangers of sound, and which for the longest time dances around what the most hazardous of them all — the mermaid’s song — might sound like.

Sounds of the industrial age, sounds of ancient enchantment, sounds which deafen, and sounds which drive men to die or to kill are implied in the moody, delicate pencil and charcoal drawings, but are for the most part left to the imagination of the reader. Like the other books above, this makes Sailor Twain an intensely reader-driven experience. Peruse it slowly, carefully, and maybe stay away from sad songs while you do.

[…] first one is from Gary Tyrell over at the webcomic news site Fleen. Gary remembers the original 2001-2003 webcomic and does a great job at examining similarities and […]

By New Makeshift Miracle Reviews | Zub Tales on 07.20.12 4:20 pm

The above comments are owned by whoever posted them. The staff of Fleen are not responsible for them in any way.